Andesite, Installation View, 2020

Andesite, Installation View, 2020

Andesite, Installation View, 2020

Andesite, Installation View, 2020

Andesite, Installation View, 2020

Danake, 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx. Jesmonite, obsidian, salt, silicone, steel, spirulina, pottasium aluminium sulphate, conch shell, wax, aluminium, dried foxgloves, red cabbage infusion, tulip wood, raw opals.

Danake, 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx. Jesmonite, obsidian, salt, silicone, steel, spirulina, pottasium aluminium sulphate, conch shell, wax, aluminium, dried foxgloves, red cabbage infusion, tulip wood, raw opals.

Danake, 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx. Jesmonite, obsidian, salt, silicone, steel, spirulina, pottasium aluminium sulphate, conch shell, wax, aluminium, dried foxgloves, red cabbage infusion, tulip wood, raw opals.

Danake, 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx. Jesmonite, obsidian, salt, silicone, steel, spirulina, pottasium aluminium sulphate, conch shell, wax, aluminium, dried foxgloves, red cabbage infusion, tulip wood, raw opals.

Danake (detail), 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx.

Danake (detail), 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx.

Danake (detail), 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx.

Danake (detail), 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx.

Danake (detail), 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx.

Danake (detail), 2020. 410 x 85 x 45cm approx.

Clockwise from top left: Gimmel (Rangitikei), 86 x 40 x 7cm approx. Silicone, steel, dried weylan blossom.

Achene 3, 202. 66 x 17 x 2cm. Aluminium, steel, thread.

Bradoon, 2020. Silicone, steel, resin, leather, silk, basalt sand, salt.

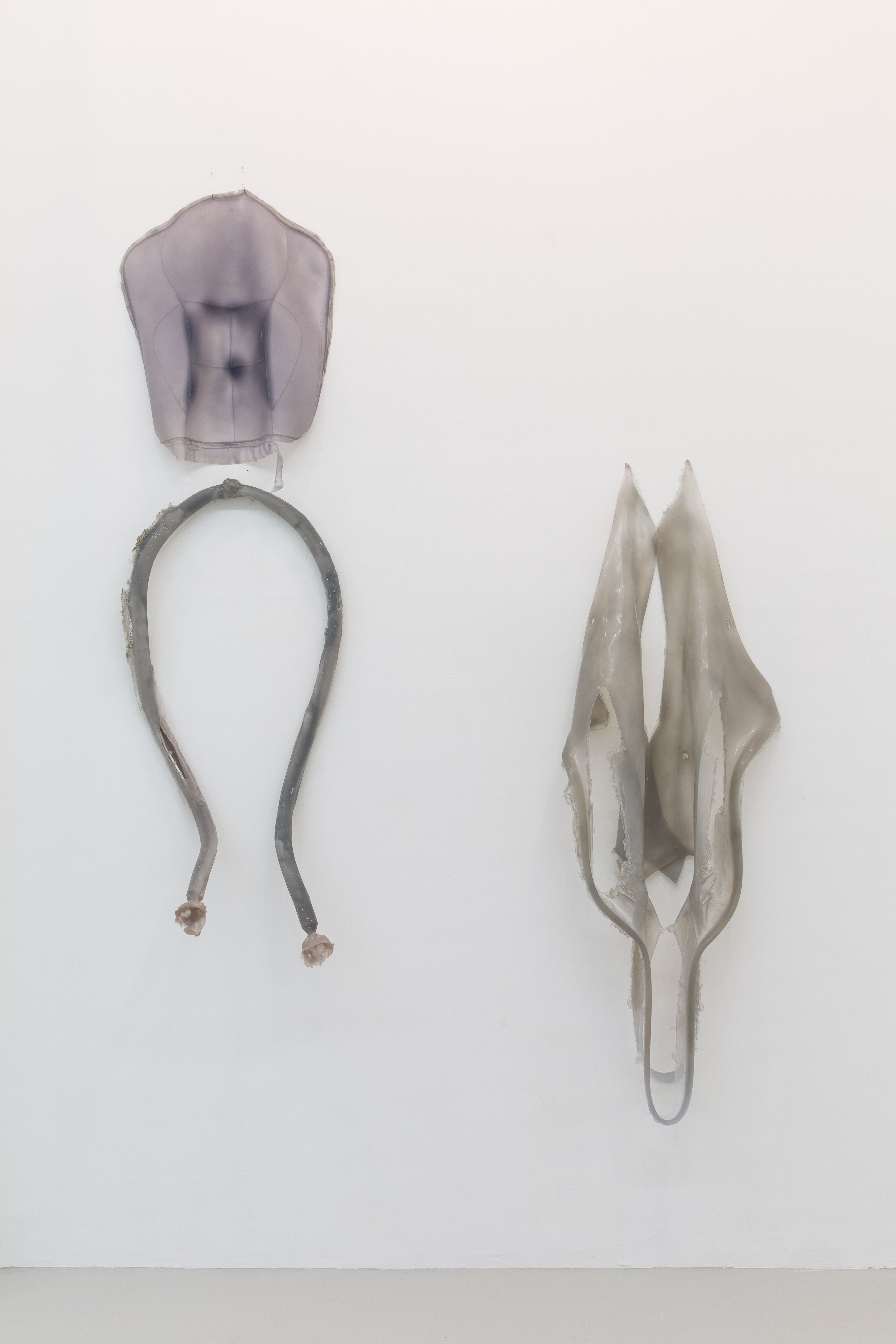

Left: Kordyle, 2020. 170 x 35 x 45cm approx. Phormium tenax, silicone, pigment, resin, ground glass.

Right: Achene 2, 2020. 75 x 25 x 10cm approx. Silicone, dried buttercups, steel, aluminium.

Achene, 2020. 75 x 25 x 10cm approx. Silicone, dried buttercups, steel, aluminium.

Kordyle (detail), 2020. 170 x 35 x 45cm approx.

Andesite, Installation View, 2020

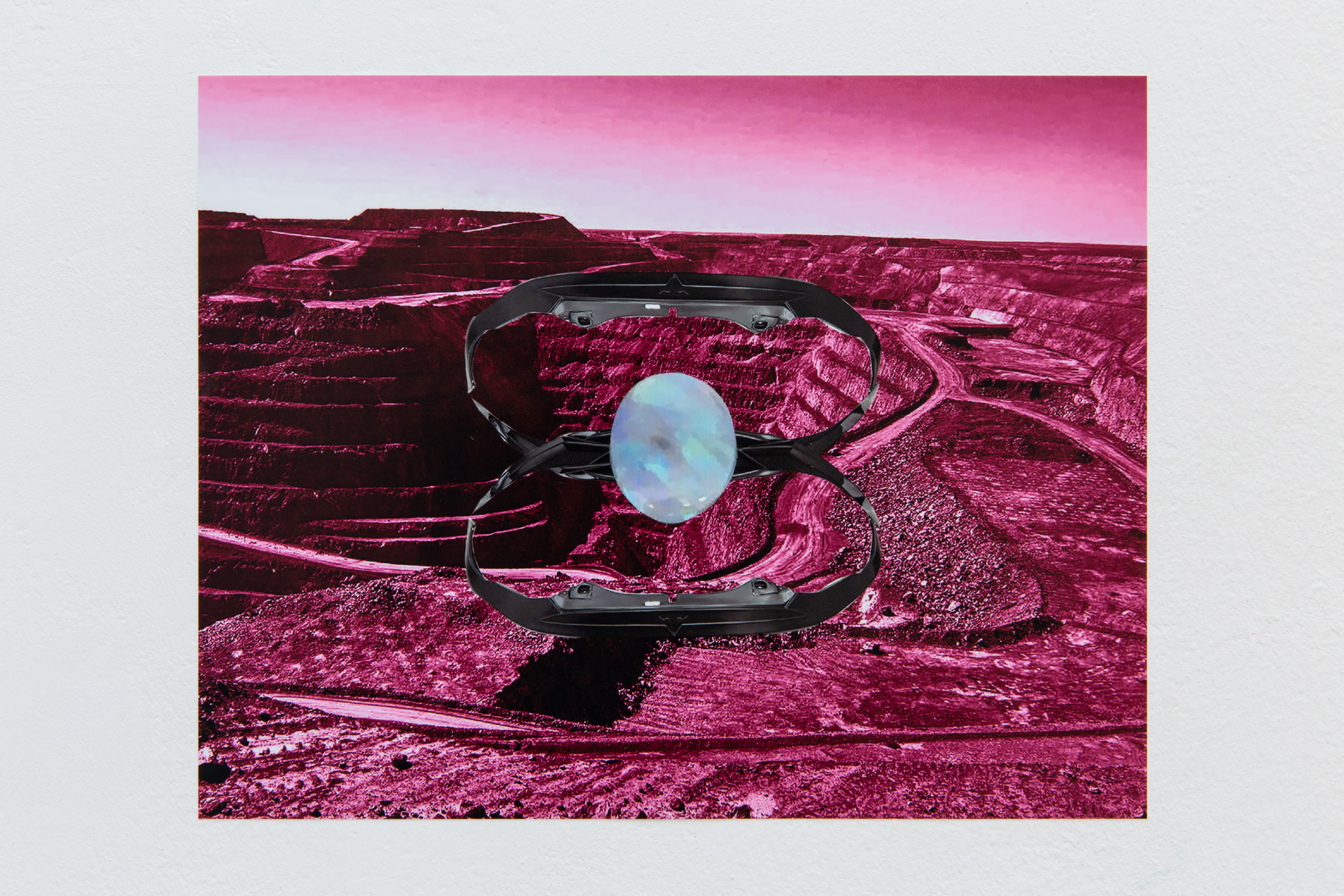

Left: Andesite (Doublet), 2020. 32 x 17cm. C-type print on paper.

Right: Achene 1, 2020. 76 x 41 x 3cm approx. Aluminium, steel.

Andesite (Doublet), 2020. 32 x 17cm. C-type print on paper.

Achene 1, 2020. 76 x 41 x 3cm approx. Aluminium, steel.

Children of Adoh (detail), 2020. 280 x 310 x 35cm approx. Silicone, steel, aluminium, obsidian, opals, basalt sand.